The artist

Life and Education

Initially, I felt a strong inclination towards graphic arts. As a boarder in a distant school, stuck during weekends, I would smear my drawings with my fingers, using pen and ink. And then, an elderly man passing by leaned over to offer me advice. It was Haffner, one of the prominent painters of the large Maritime Museum of Paris from the 1930s to the 1950s, much like Marin-Marie. However, this path was prohibited for me. The very traditional family environment demanded a focus on achievements from prestigious institutions. Art was considered important, but it was meant for personal enjoyment, done discreetly on the side. I had a particular interest in maritime subjects, especially beautiful ancient sailboats. I began to frequent antique shops.

Professional life played a significant role. I was well-served. Holding high positions in major corporations, I even had a stint as a general manager in New York for five years. The pivotal moments began with marketing training at the world’s largest advertiser. Subsequently, I accumulated a toolbox of management skills across various domains, particularly from prominent consultants. Then, starting from 1975, I acquired technologies from major client accounts. I developed specialized expertise in organization, competitive foresight, databases, scheduling, creativity, and more. And it was here that an idea started to take shape: to transpose these advancements into art. My contracts sent me across the globe. I seized the opportunity to visit museums everywhere, especially those focusing on the 18th century and maritime themes. Even as far as the Maritime Museum in Auckland, New Zealand, for instance…

How I became a painter

And that’s how I gradually became a painter without even realizing it. I painted for myself. However, encounters in the world of prestigious antiquarians first served as practical training in art history and then led me to research for them, reconstructing 18th-century paintings shows. From there, I delved into the realm of second-circle painters—those who worked for the elite, too preoccupied with the Court. I discovered great talents, especially when they were working for themselves. I was able to acquire beautiful works of art. And I began to blend my own drawings with this approach. Over time, my antiquarian friends would take my drawings in exchange for their professional insights. I had just purchased a magnificent, unknown painting by Joseph Vernet (1714-1789); struck by its sky and the quality of its distant elements, I vowed to achieve the same results. It’s feasible, especially when you have the work constantly before your eyes.

In reality, I was becoming skilled enough that during the inventory of a major business figure in New York, a friend recounts how an expert once attributed two of my period-framed watercolors from the 18th century to a prominent artist of the time, a gift I had bestowed upon him.

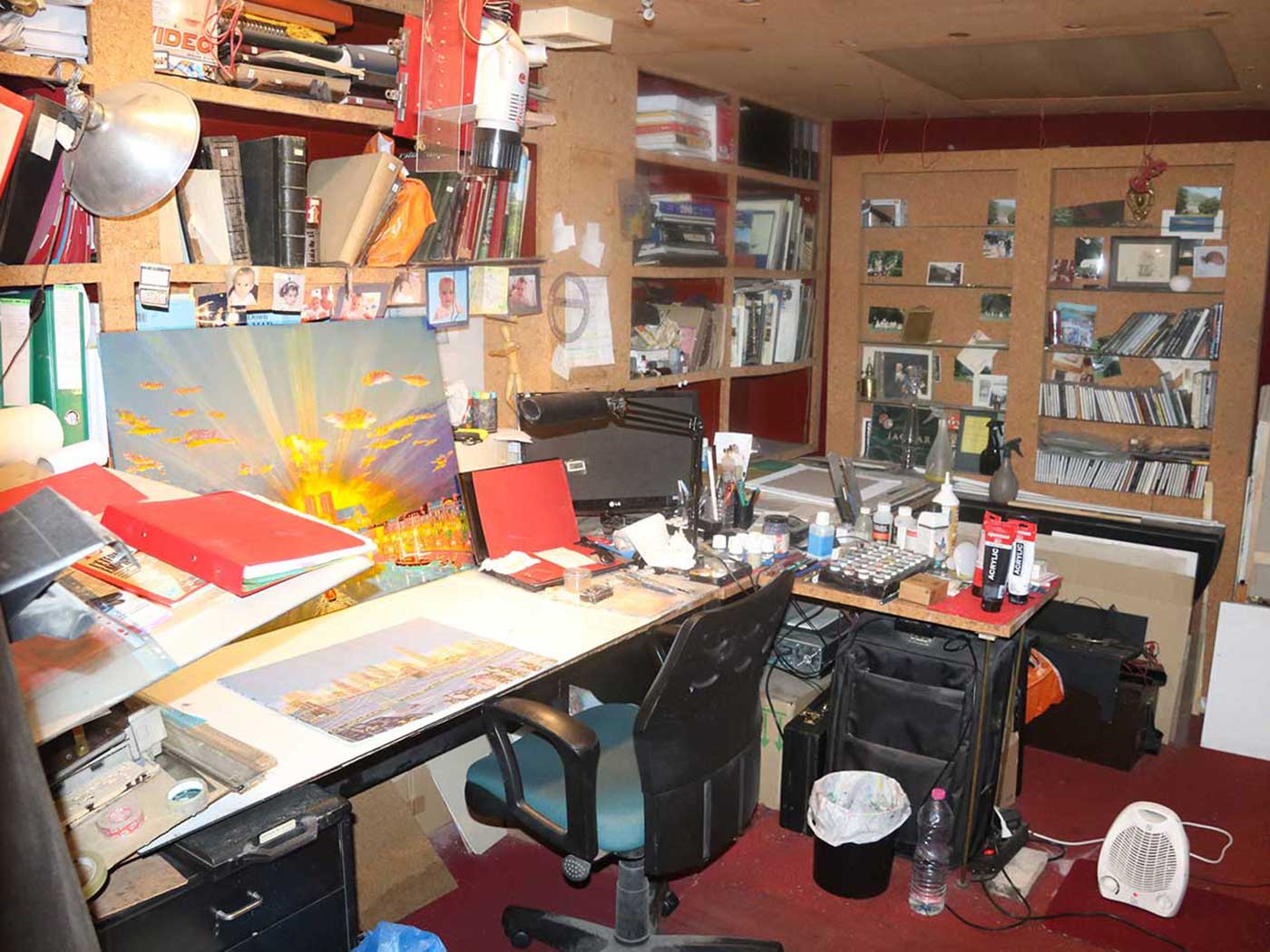

Over the years, I joined other painters in collaborative workshops (Versailles). I began by painting hundreds of watercolors, advancing in creativity, technique, poetry, and themes (maritime scenes, landscapes, urban views). Then, I moved on to oil painting, where drying times became a significant challenge, even for an artist with no economic constraints.

My objectives

There came a point when, freed from professional obligations, I embarked on a more decisive period of contemplation. It was evident to me that contemporary art was heading towards a crisis of emptiness. Modern artists were increasingly moving away from highly decorative abstract models towards a more and more vacuous “conceptual” approach, often merely provocative. Provided, of course, that these works could be produced very rapidly. Our professional guides in collaborative workshops seemed tempted by a return to the old standards of quality, but it demanded a significant investment of time. They appeared to be quite unaware of the parallel worlds of industry and technology.

So, what could my new objectives be? I had already made progress on a novel proposition, neither impressionist nor modern, and had advanced to creating numerous highly distinct paintings, drawing from entirely different sources.

I participated in very few exhibitions, investing my time in the pursuit of quality. I had only exhibited in Manhattan, at the renowned Kennedy Gallery (Madison Avenue). Local municipal exhibitions for non-professional painters brought an influx of positive and encouraging feedback: “singularity, evocation of positive emotions.” I also paid heed to my American friends, whether they were gallerists or enthusiasts. Hence, I needed to seek recognition, to connect with decision-makers and art lovers. Anything that could provide useful encouragement to bolster my efforts. Nevertheless, I must always remain humble throughout these endeavors.